Welcome to the Verbatim Blog - a space dedicated to expert proofreading and editorial insight. Here you’ll find practical writing guidance, academic tips, publishing advice and reflections on language, clarity and style. You will also find examples of my own writing - which will give you an idea of my versatility. New posts are added regularly and written by Evangeline Bell, Intermediate Member CIEP and PTC-trained proofreader.

A coal miner’s son

Corporal Jack Booth watched the new POWs file into the hall. They sat in rows on hard wooden chairs and faced Major Wilkinson, the camp’s commanding officer.

As the Major politely, but firmly, outlined their current status as POWs under the provisions of the Geneva Conventions and explained how the camp operated, Jack Booth studied the faces of the men whose war was now all but over. He decided that the overwhelming mood was a mixture of relief and confusion with, perhaps, a tinge of apprehension. A lot were very young, obviously conscripts who were probably just glad to think that they might live to survive the war. Some were veterans, weary but tougher: more resilient. Some of those youngsters looked as if they might burst into tears at any moment with the sheer emotional overwhelm of it all. One or two looked wary. Their eyes shifted as they took in the details of the scene. All the prisoners would eventually be interrogated and Jack wondered if these were the ones who might actually yield useful information. It was highly unlikely that the conscripts could reveal anything but their names and units.

One man stood out. He wasn’t tall but he sat erect. He had an air of authority about him: an aura of self-confidence, even arrogance. This man looked to be in his late 30s. He wasn’t a hardened veteran but nor was he a green youth. Despite the limitations of POW status, there seemed to be something cultivated about him, as if he did not quite belong in this situation. He was clearly weighing things up. Corporal Booth decided that, despite wearing no insignia denoting officer rank, this man probably was an officer - but, for an unknown reason, was not in his right uniform.

Corporal Booth was very wrong about this. Friedrich Von Altenburg certainly carried himself like an officer. He had the archaic name and ancient lineage of an officer. But he was not an officer. He had been a very reluctant conscript. This was not because he was unpatriotic or even because he was disloyal to the Nazi regime. If he had been, he’d have ended up in Sachsenhausen. No: Von Altenburg simply thought that fighting in an army was beneath him. He thought of himself as an ultra-civilised man, cultured, learned and enlightened. He did not belong in a uniform. As a result, he had held out to remain in civilian life as long as the regime had permitted - but, eventually, he had had no choice but to reconcile himself with the inevitable. And here he was: a POW with the lowly rank of Gefreiter. He was now beginning to wish he’d shown more enthusiasm for military service; if he had, he’d probably have found himself in an officers-only camp where, protected by the Geneva Conventions, he would not be required to do manual labour. Instead - this English Major was telling him that he was going to be digging potatoes - or something equally serf-like - while these working-class British tommies stood watching. He felt the humiliation keenly.

Life at Camp 227 - or, as the local villagers called it, ‘Low Fell Camp’ - was monotonous. Major Wilkinson ran a tight ship. Everything was done according to regulation. Prisoners were treated fairly and, for the most part, they spent their days doing agricultural work on local farms. No, they were not free - but they were safe and the level of security was not excessive. On arrival, prisoners would be routinely interrogated but, after that, their days became regularised: early reveille, roll call, breakfast, work, midday meal, work, evening roll call and then a couple of hours leisure time before lights out at 9.30. Von Altenburg found the routine tedious in the extreme. And, to alleviate his boredom, he began making trouble.

He wasn’t putting his mind to devising escape plans. What was the point? Britain was an island and there would be no way back to the European mainland without crossing a water that was totally under the control of the Royal Navy. And that was assuming you could even make it to the coast at all. Britain was not occupied France or The Netherlands, where an escapee might find a sympathetic civilian population or an organised resistance movement ready to help. The first Britisher to suspect would report you straight to the authorities. Escape was an absurd idea. Besides, Von Altenburg knew that he was probably safer in Camp 227 than anywhere else.

No: Von Altenburg wasn’t intent on escape. But he resented having to kowtow to the petty authority of these peasants in khaki. So, he put his mind to finding ways to defy them and to assert his superiority over them. It helped that his English was superb. As soon as his fellow prisoners became aware of his fluency in the language, they looked to him to represent them with the English officers. It was Von Altenburg who was deputised to approach Major Wilkinson regarding matters relating to food, letters from home and work. He also asked permission to teach English classes to those prisoners who wanted to learn. The Major happily gave permission … and this gave Von Altenburg the outlet he needed. He taught English well enough but loved to do so in a way calculated to annoy the English guards.

He particularly enjoyed baiting Corporal Booth whose thick Yorkshire accent grated on his ears. The oaf could barely speak his own language so Von Altenburg didn’t bother to conceal his contempt as he taught his pupils to pronounce English words in a very clipped and precise manner. He chose sentences which were calculated and insulting for the men to practice their grammar. ‘Double negatives’ said Von Altenburg, ‘are incorrect. It is not “I didn’t do nothing wrong. It is “I have not done anything wrong.”’ He was sure that the stolid Booth knew that he was being laughed at but incapable of understanding the joke.

Von Altenburg was very wrong about that. Jack Booth was certainly Yorkshire born and bred. His father had been a coal miner and, very likely, that would have been Jack’s fate, too, had he not chosen to become a soldier in the mid-1930s. Jack was not a conscript. He had watched his father cough black sludge from his lungs while still a young man and decided that while soldiering might carry risk, it was better to be killed quickly than to die the long way. Jack had served in Palestine prior to the outbreak of war. He’d been at Dunkirk in 1940 and in Egypt by 1942. Army life had been good to him but, after contracting diphtheria in early 1943, he had ended up being posted to Camp 227 as a guard instead of returning to front line combat duties. Jack may not have had much of an education as a boy, but he was no fool. He recognised exactly what Von Altenburg was doing.

Major Wilkinson tapped his cigarette irritably on the ashtray. MI19 were causing a nuisance again. The letter which lay open on his desk informed him that owing to Camp 227’s failure to notify them of any prisoners suitable for detailed interrogation for the past three months, a Captain David Markham would be paying them a visit to assess the situation for himself. Damn! Wilkinson ran an orderly and peaceful camp. His job was to ensure that work parties were provided for the local farmers and that no prisoners escaped. That was it. He did not need some jumped-up university-educated whizz-kid coming and causing disruption to the camp by hauling off random prisoners to who-knows-where and upsetting the rest. Besides, most of his inmates were nothing more than ignorant conscripts. They’d know nothing of any military or strategic use. It was all just unreasonably annoying.

‘Corporal! Corporal!’

Booth entered his commanding officer’s room. ‘Sir?’

‘We’re going to have a visit from Intelligence. They want some prisoners to interview. Apparently … we haven’t been sending them enough recently.’

Corporal Booth looked at the Major. ‘Most of these lads are nowt but conscripts. They don’t know nothing.’

‘Yes. But we will have to give “intelligence” …’ This last was said with a suspicion of a sneer. ‘… something. Any suggestions?’

Booth thought immediately of the supercilious Von Altenburg. ‘The one who gives English lessons. He can speak our lingo.’

Wilkinson nodded. He should have thought of Von Altenburg himself. Mind you - these cocky intelligence officers liked to show off their German. Maybe Markham would prefer something he’d have to interrogate in German? He could give him that shifty-looking creature who always hung back after roll call. He might not be much but he, at least, looked vaguely suspicious. There was nothing suspicious about Von Altenburg. He kept his nose clean, worked compliantly and gave English lessons to the other men. That had proved to be invaluable. His own German was passable but basic. It’d had become a lot easier to communicate with the prisoners since Von Altenburg had been there to translate and to teach the men the meaning of basic instructions in English. The only odd thing about Von Altenburg was that he seemed too … too posh to be in a regular POW camp. He seemed more like an officer than a ranker. Wilkinson didn’t want to lose him. Still - it wouldn’t do any harm to let Markham talk to him for an hour or so.

When Captain David Markham arrived, he was respectfully saluted by Corporal Booth and promptly escorted to Major Wilkinson. Markham was much younger than seemed entirely reasonable for an intelligence officer. He was pleasant and polite with an airy charm. He wore a neat moustache and seemed anxious to make an impression. What Wilkinson and Booth did not know was that this was Markham’s first really solo mission. He’d been part of the intelligence team at Trent Park for some 12 months now, but this expedition to Camp 227 was the first time he’d been asked to carry out an operation entirely by himself. He was confident in his ability, his education and in his training, yet also slightly anxious. He wanted to do well - and that meant finding out some useful nugget of information to take back to his superiors at HQ. Wilkinson at once pigeon-holed him as an upstart with no real military experience to speak of.

‘So, Major, what have you got for me?’

‘We have a few you might be interested in. But, for the most part, these men are rank and file conscripts. Few speak any English …’ The Major’s voice tailed off.

‘Oh - that’s not a problem,’ beamed Markham, ‘my German is … “wunderbar.”’

Wilkinson’s left eyebrow shot up but he said nothing. Booth, standing quietly in front of the door, smiled to himself. ‘Excuse me, sir’ he interjected. ‘And Herr Von Altenburg.’

‘Ah! Yes. Thank you for reminding me, Booth. Yes. We do have a prisoner who is a fluent English speaker. He often translates for us. You should speak to him, too.’

‘Delighted to, I’m sure. But I won’t need a translator.’ Markham seemed very confident in his linguistic skills. And so, it was with this spirit of optimism that Captain David Markham began his interrogations - with Corporal Booth assigned to assist him.

They used one of the small rooms which opened off of the same narrow corridor which led to Major Wilkinson’s office. There wasn’t much in the way of spare accommodation in Camp 227. It was tiny and dark, with only a single, unshaded, electric light bulb hanging in mid-air. There were no windows and it felt more like a broom cupboard than an office. The corners were so dark that they disappeared entirely. Markham placed a table between himself and the prisoner and they sat facing each other. He held a notebook and pencil and scribbled copious notes as each prisoner was asked, and answered, the same list of standardised and prepared questions. Booth listened attentively. Markham’s German was, indeed, grammatically perfect.

But the information he was noting down in his tiny, cramped handwriting was utterly useless. Most of the men he interrogated knew, as he and Major Wilkinson had both anticipated, nothing of any strategic value whatsoever. And, if they did, they talked - but revealed nothing. As the days passed, Markham’s disappointment became ever more apparent. He would begin each interrogation with the same brisk tone, but the pencil would start to hover and then droop before it was discarded entirely. Instead, the ashtray would start to overflow and the tiny room fill with curls of smoke. They floated and swirled in the yellow electric light of the bulb, obscuring the prisoner from his interrogator.

After some five days of this tedious futility, Friedrich Von Altenburg walked into the room. He stared at Markham, and then at Booth. In German, he asked what this piece of scum (he was referring to Booth) was doing there. Markham replied, in perfect German, that he was there to assist and to ensure that no prisoner was maltreated during the interrogation process. That had been at Major Wilkinson’s insistence. Markham had never had any intention of maltreating a prisoner but Wilkinson was not going to trust the word of this irritating young man. He believed that it was his duty to stick to the letter of the Geneva Conventions and had posted Booth to assist Markham along with strict orders that the corporal should report any irregularities to him immediately. There were no irregularities to report. But there was no useful military information to report either.

Von Altenburg gave Booth a look of pure disdain and seated himself opposite the Captain. He switched into English. ‘And how may I be of service to you, Captain?’ Markham momentarily looked taken aback but, covering it swiftly, he began to ask the questions which Jack Booth already knew by heart. Von Altenburg responded calmly, politely, predictably - and facetiously. Markham didn’t appear to notice the asymmetrical lip lift which told Booth that he was treating the entire process with contempt. He was just delighted to have a prisoner who appeared to be giving him solid information - at last. His scribbling became more ferocious as Von Altenburg talked.

Jack Booth stood stoically in front of the door. He said nothing but, quite clearly, saw the gleam in his eye. Von Altenburg was lying. He was sure of it. He was making up a complete tissue of lies - but why? Did he have real military knowledge that he was hiding or was he just enjoying making a fool out of this eager young Captain? Booth did not know. What he did know is that Von Altenburg was lying.

And that irritated him.

Shortly after midday, Markham left to take a phone call. Booth silently watched Von Altenburg for a while. Eventually, he said, without a single trace of his broad Yorkshire accent, ‘Die Wahrheit zu sagen ist eine Pflicht, die man gegen jeden hat.’

Von Altenburg’s eyes widened in amazement. He said nothing.

Booth continued, this time in his usual broad and accented English. ‘Kant did not believe that war overrides ethics. How is it possible that the same people who produced Kant now treat Hitler as their Messiah?’

Von Altenburg shifted uneasily. Did Booth know? How could he know? As a young student, Von Altenburg had loved the works of Immanuel Kant. All educated Germans were well-versed in Kantian ethics. True: they had been sidelined during the last ten years and conveniently forgotten as the war had intensified. But, deep down, Von Altenburg remembered …

Booth continued to talk. Against his will, Von Altenburg found himself answering. To his own irritated surprise, he found himself quoting Nazi propaganda: ‘War’ he said, ‘was a law of nature. Life was all about the survival of the fittest. War determined who deserved to thrive and who deserved to be eliminated.’

‘That’s not very “German”.’ said Booth, placidly. He moved out of the shadows to sit in the seat across from Von Altenburg which had recently been vacated by Captain Markham.

‘What can you possibly know about what it is to be “German”?’ said Von Altenburg.

‘I know that Kant did not believe that violence justifies immoral actions or that you can establish what is right by force. He said, “Kein Frieden kann für einen solchen gelten, der mit dem geheimen Vorbehalt eines künftigen Krieges geschlossen worden ist.” And that’s what Hitler did at Munich in ‘38 and with the Russians in ‘39. Hitler is no “German”.’

That stung Von Altenburg.

‘Versailles was an abomination. We had a right to regain our national dignity.’

‘And how, exactly, does the kind of warfare you’ve been conducting do that?’ said Booth. ‘How does the bombing of cities full of civilians and the destruction of European civilisation itself help to restore Germany’s “national dignity”? Give me just one example of how Germany’s conduct in this war can possibly do that.’

And, at that point, Von Altenburg really began to talk. He talked rapidly and in abstract terms. Booth didn’t interrupt. He just let the incensed Von Altenburg vent. Then, slowly, he began to ask for examples. Could Von Altenburg tell him whether he ever thought that a commander remains morally responsible for the consequences of an order once it has been carried out, even when those consequences were not explicitly intended? Could he give an example from his own experience?’

Von Altenburg could … and did. And was in full flow … as Captain Markham reappeared. This could have brought an abrupt end to the conversation but neither Jack Booth nor Friedrich Von Altenburg noticed the captain as he slipped back into the room. For one moment, David Markham was on the verge of interrupting. Then, he realised what Von Altenburg was actually saying. Silently, he stepped back into the dark shadow of a corner, took out his notebook and began writing.

Corporal Booth continued the interrogation.

As the wound-up and agitated Von Altenburg tied himself into impossible philosophical knots, the self-educated son of a Yorkshire miner, who had whiled away many a tedious day in pre-war military barracks reading whatever books he could find, intuitively peppered Von Altenburg with the kind of questions which enticed him into revelations of his wartime experiences. No - as a mere Gefreiter, Von Altenburg was not privy to high-level military strategy. But he was a clever man who could interpret what he saw. He now used those experiences to illustrate what he was seeing as a philosophical debate on the justification of Germany’s war. It was not so much Nazi propaganda as his personal moral shield. He had not wanted to fight at all. Deep down, he agreed with Kant: war was a consequence of moral failure, not a matter of national pride. But he had found himself in an impossible position and, in the face of Corporal Booth’s philosophical provocation, he sought to justify his own actions to himself.

By the end of the afternoon, he was exhausted. He fell into silence. Booth smiled; he was very satisfied with his day’s work. Markham stepped forwards. ‘Sorry to interrupt you, Corporal, but I think it’s time we all had a cup of tea. What say you, Herr Von Altenburg?’ The German POW startled as he noticed Captain Markham’s presence for the first time in several hours. His eyes fell on the notebook as Markham closed it shut … and he knew exactly what he’d done. As he was escorted back to his bunk room, Von Altenburg turned to look at Corporal Booth. Their eyes met and Booth gave the German corporal a smart salute. Von Altenburg grimaced.

Major Wilkinson looked stunned as Captain Markham slid his pad of closely written notes into his briefcase. It had been an incredibly successful few days, thanks to … Corporal Booth. His afternoon with Gefreiter Von Altenburg had yielded more information about German weaponry and battle tactics, command decisions and logistics information than any interrogation which Captain Markham had ever participated in or witnessed. It wasn’t strategy at its highest level. It wasn’t top secret information. But it was useful. And just watching Booth’s technique had taught him a lesson. He had realised, almost in an instant, how sterile his standardised questions were in comparison to the dynamic dialogue adopted by this corporal - and he looked at the corporal with a new level of genuine respect.

What Wilkinson mostly wanted to know is where had the son of a Yorkshire coal miner learned German. ‘Palestine, sir’, said Corporal Booth. ‘Before the war.’ He explained that there had been a German doctor doing medical work in one of the villages and Booth had been posted there as part of a detachment sent to protect the medical facility from terrorist attack. He had got to know the doctor well and had started to pick up a bit of German. He found that he loved the words and the rhythm of the language. The doctor had been pleased with the young soldier’s talent and with his enquiring, but obviously undeveloped, mind. They’d talked - and Booth had learned both the German language and something of German history and culture. Later, to alleviate the boredom of barrack life, he had read Kant and other German works. It had been his ambition, he said, to visit Germany itself but the war, and then his illness, had put an end to that.

Captain Markham smiled warmly at Booth. ‘You’d make a fine intelligence agent, Booth. Why did you never tell anyone of your fluency in German?’

‘I’m a soldier, sir. Not a spy.’

Meanwhile, in Hut 3, Friedrich Von Altenburg ruminated. He couldn’t quite explain what had happened. At one point, he’d been amusing himself toying with the young captain and, then, that ‘Landei’ had tricked him. He twitched uncontrollably and he thought of Kant: “Der Mensch darf niemals bloß als Mittel, sondern muss jederzeit zugleich als Zweck gebraucht werden.” “A human being must never be used merely as a means, but must always be treated at the same time as an end.” To Kant, a person’s worth lay in their moral disposition, not their social position. Booth had been right: Nazism wasn’t “German” - and he wasn’t sure which was more intolerable, that Hitler had subverted German morals or that he had learned this lesson from a Yorkshire coal miner’s son.

Corporal Jack Booth and Gefreiter Friedrich Von Altenburg

For proofreading and editing of fiction or non-fiction contact Verbatim.

Precision. Clarity. Verbatim.

01 How to make learning easy: patterns of meaning

I spent over 30 years in education. I did this because I passionately believe in the value of learning and that every child should have the chance to learn. Learning is the foundation of civilisation and of human progress. It is the means whereby potential is revealed, and innovation and creativity are unleashed. Without learning, neither the moon landings nor the internet: neither the 1812 overture nor Bohemian Rhapsody would have happened or exist. Monarchies would not have given way to liberal democracy, capitalism would not have replaced feudalism and we’d all be trying to scrape along at subsistence level. It matters for culture, economic development, society and government. I didn’t spend 30 years wasting my time: I worked in an incredibly important profession.

More prosaically, those little bits of paper which are the public examinations are the keys which unlock doors for individuals in the modern world. It matters a great deal that children enter adulthood with ‘grades’ simply because that is what the world looks at before it looks at anything else. Many a great candidate for a job never makes it to interview because they’re screened out for not having an appropriate qualification.

Nevertheless, the teaching profession often makes the art of teaching more obscure than need be. It loves jargon and acronyms, models and frameworks. Schools are institutions and those who run them love uniformity, systems and processes. The word ‘consistency’ is bandied about perpetually. And the result is that the basics of how learning is actually engendered is often lost in this sea of micro obsessions. This series of blog posts is aimed at stripping the art of teaching back to its basics and remembering that human beings are learning machines. It’s arguably harder to stop children from learning than it is to get them to learn. Of course, what children learn may not always align with what the teacher wants to teach - but they will learn something.

This series of blog posts, originally written between 2022 and 2025, is about how to make it easy for all children to learn - and for them to learn what it is that their teachers intend them to learn efficiently and effectively. It is about deliberately constructing a purposeful learning experience.

How to Make Learning Easy: Patterns of Meaning

Learning shouldn’t be hard. Of course, everyone comes across something they find difficult at some point and there will always be those who struggle. But, for the vast majority of students, the process of learning things should not be hard because human beings are learning machines. We’re built to learn.

It’s impossible to remember a list

In a training session I attended many years ago, we were asked to memorise a list of objects. It was after the end of the school day and, in our group, we were all tired. I remember that I was particularly bad at it. However, there was a serious point and that was that it is almost impossible to learn things if they are presented as a list of items with no form or shape. This is absolutely true. During my teaching career, I managed to raise GCSE History grades in two different schools, not just a little bit, but by 30-40 % points. When I arrived in each school, one of the problems was exactly this: teachers had been attempting to teach subject content using chronology as the only organising mechanism. Essentially, it meant that they had been trying, and largely failing, to get students to learn ‘facts’ in a very long list.

The training session then lost momentum as it went off down a rabbit-hole of a list of clichéd micro-strategies for memorising. And the most important point was missed by a country mile. First, the real problem is less one of memory than one of recall. And, second, when it does come to memory, it is necessary to recognise that everything is learned in relation to that which is already known.

Patterns of meaning

Every subject discipline has its own patterns of meaning. When we refer to ‘disciplinary language’ that’s what we are really talking about. It is that language which encodes the patterns of meaning which are intrinsic to that subject. Experts in that subject (and that means all specialist subject teachers) have an intuitive understanding of those patterns which has come from years of study and practice. It means that when teachers are presented with some new information related to their subject, they intuitively fit that knowledge into those pre-existing patterns. They absorb it easily. It is easy for them to learn.

The students we teach are not in that position. Not, that is, unless we first teach them the patterns of meaning within our subjects. This is what I’ve always done in History - and this was the hidden reason why I was able to improve GCSE outcomes so dramatically. The GCSE in History has always been content-heavy. If our students were to have even a fighting chance of retaining (let alone recalling) all that knowledge, they needed to be able to fit it into pre-existing patterns of meaning. Anything which diverted their attention from that had to be discouraged. For this reason, I’ve had very little patience with classroom micro-strategies which look and sound impressive, but are, in the end, superficial. It matters not whether min-whiteboards, hinge questions or collaborative learning techniques are favoured; what matters is whether the students internalise the core patterns of meaning which are the principal organising structures of the subjects they are attempting to learn. The technical term for this is ‘mental schema’. What I am arguing is that substantive content is more easily understood if the learner has already assimilated the mental schema which is intrinsic to the subject being learned. This is what we mean by metacognition.

One final point on this is that those students who really struggle with their learning are invariably those who struggle to identify patterns. That’s what the whole idea of the non-verbal reasoning part of a cognitive aptitude test is supposed to identify. Therefore, an important feature of any teaching programme has to be to make sure that students who are weak in terms of non-verbal reasoning internalise simple patterns. Focus less on ‘scaffolding’ tasks and more on embedding patterns. Without them, students will be lost at examination level - and those students who struggle most with identifying their own patterns will definitely struggle most under the pressure of an examination.

Early assessment should focus on patterns, not content

It is important not to confuse the concept of ‘patterns of meaning’, or mental schema, with ‘skills’. It may well be that there are patterns of meaning within your subject which are also skills but they may equally be related to concepts or knowledge. Nevertheless, whatever your patterns of meaning are, that is what you should be assessing in the early stages of your curriculum plan. Don’t waste time assessing everything you’re teaching, especially in the early years of secondary school. I never tested student knowledge of every topic we taught in Y7-9. Most of it would never form part of the sampling process of a GCSE exam and, for me, this was not the purpose of the curriculum at that point, so where was the sense in testing for it? What I assessed, in a frequent and regular way, is whether the students were retaining those essential patterns of meaning which are the core of our subject. I knew that, if they were, then it would be a whole lot easier for them to slot in the knowledge both needed for the exam later on, and for that greater purpose of understanding the world around them. Even more importantly, teaching children the importance of identifying patterns is better preparation for the adult world where problem-solving and innovation are needed far more than banks of facts. This is even more important if education is to prepare children for a future in which change is inevitable but the nature of that change unpredictable.

I want to be clear, however, that I am not denigrating the importance of ‘knowledge’. Rather, I am arguing that substantive knowledge, meaningful knowledge, knowledge which can be used and applied in a variety of contexts or to solve problems, can only really be internalised and retained if it is learned in relationship to ‘patterns of meaning’, or mental schema. This series of blog posts is about how to make the learning of that knowledge easy.

It is for this reason that a strategy of frequent knowledge testing never worked for me. Such tests are a form of knowledge sampling. The theory is that constant testing will force the students to learn how to revise. It is a sledge-hammer to crack a nut, in my view, a massive workload and a lot of wasted effort on the part of both teachers and students. It derives from a fundamentally shallow understanding of the learning process. We first need to assess the extent to which students are forming and retaining the relevant patterns of meaning for our subjects. There’s a time for knowledge sampling – and, from the point of view of student outcomes, that time is during the examination course, especially as we draw close to its conclusion. From the point of view of subject understanding, it is at the point where the learner is automatically using an embedded mental schema to make sense of new information.

Merely assessing student knowledge at the end of a topic is neither knowledge sampling, nor is it testing cumulative retention. It is only assessing recent understanding or, at best, short term retention. Its usefulness is pretty limited, actually. Far better to adopt a longitudinal approach. Begin by assessing the extent to which students are internalising the mental schema: the fundamental organising patters of meaning in your subject. By all means, use your latest topic as the vehicle but remember that it is not the topic which matters but the patterns. Then, gradually, move towards synthesising this with substantive knowledge. What we’re looking for is for students to be able to apply those patterns of meaning to ANY topic in your subject - independently. And, as the examinations draw closer, for students to be able to deploy those patterns as a mechanism for retaining substantive content. Trust me: it’s far easier to retain content if those patterns are solidly embedded in the long-term memory.

Thus, once you have identified the core patterns of meaning (and there might well be knowledge patterns in there), then that is what you should be laser-focused on assessing. It will all make it so much easier for the students to learn everything in the end.

Conclusion

Learning should not be hard work. That is not to say that hard work won’t reap rewards. It will. But - it is quite possible to work hard and achieve very little.

It is a far more efficient means of learning to build a curriculum plan which overtly teaches your students what you already know intuitively - the patterns of meaning which are an embedded part of your subject discipline. Then, later on, you can teach them new content and it will be both absorbed and understood.

If you publish books or educational materials, Verbatim is here to help, not just with proofreading but with professional expertise.

Precision. Clarity. Verbatim.

I broke

The clouds shivered;

Nature gasped in sympathy;

The ink-stained map vanished

And I was struck dumb.

I, whose words flowed,

Was as a stoppered flood.

All tense and taut in misery

I broke - and they could not come.

Think about the words chosen in this poem and what work they’re doing to create the image:

shivering clouds

An adjective-noun combination which actually gives an unnaturalness to the poem. Clouds do not ‘shiver’. They might ‘drift’ or ‘float’ or ‘race’ - a movement which conveys the idea of motion. ‘Shivering’ conveys the idea of an uncomfortable and unnatural stillness. This signposts what the poem is about - a person who is so psychologically broken that they can no longer express themselves - or behave in a way which is ‘natural’ to them. Clouds which ‘shivered’ would, similarly, be broken.

nature gasping

ink staining

words flowing

a flood stoppered

These are all combinations of nouns and verbs. Verbs are suggestive of ‘action’ but these actions don’t lead anywhere. Just as clouds do not, in reality, ‘shiver’, so nature cannot, collectively, ‘gasp’. Ink might stain but it doesn’t communicate for the map ‘vanishes’, and the flowing words are ‘stoppered’. The image of a ‘stoppered flood’ suddenly turns this unnatural stillness and the sense that things are not right into a tension - and the idea that this state of affairs cannot last. A flood cannot be held back by a tiny cork.

tense and taut - alliteration used to reinforce the meaning and double-down on the sensation of tightness and tension.

Now, look at the punctuation:

The first two lines of the first verse end in semi-colons. This has the impact of layering the three images on top of each other.

In the second verse, we have commas used to insert a subordinate clause which helps to create that tension between the ‘flow’ and the ‘stoppered flood’.

The dash after ‘broke’ then creates a physical representation of the meaning - the ‘breaking’ of the writer.

There is only one clear rhyme - ‘dumb’ and ‘come’. These are situated at the end of each verse. They are a pararhyme, rather than an exact rhyme, and slightly ugly. This matches the meaning of the poem. Situated at the end of each verse, they create a feeling of backwards pressure into the rest of the piece. They also create a feeling of closure: nothing moves, nothing arrives. Sound loops and stops. They seal the poem shut acoustically.

The poem isn’t written with a consistent meter. It’s dominant rhythm is an iambic pulse but it is really written in free verse with truncated and spondaic endings to enact psychological pressure.

All of these features illustrate prosody at work: lexical choices, punctuation, rhyme and meter.

Verbatim can help you with proofreading which is super-sensitive to your author’s voice, whatever it is that you are writing.

Precision. Clarity. Verbatim

Prosody - how we hear language

‘The ear is the only true writer and the only true reader.’

Robert Louis Stevenson

When we read, we hear.

Not aloud, but internally. A voice forms in our mind, complete with rhythm, emphasis, pauses, and emotional inflection. This phenomenon is not accidental. It’s called ‘prosody’. This is the way we hear language: it is, if you like, the musical architecture of language.

Prosody is usually discussed in relation to speech or poetry, but it is just as vital to prose. When any writer writes, he or she is trying to convey their own voice in written form. In fiction, the writer is telling themselves a story. Dialogue is phrased and emphasised in their own heads. Descriptions and actions are told in a certain way. The challenge for a writer is to enable the reader to replicate that voice as they read.

In non-fiction the voice may be different, but the challenge remains the same: to enable the reader to hear the voice of the author as they read.

There are a number of different tools which can be deployed from the writer’s toolkit to achieve this goal. But, arguably, the one which has the most impact is punctuation.

Punctuation as acoustic instruction

Punctuation tells the reader how to move through a sentence, where to pause, where to lean in, and where to stop. Here are some simple illustrations:

· A comma introduces a light pause.

· A semicolon sustains a thought without breaking it.

· A colon creates expectation.

· A dash disrupts, interrupts, or adds pressure.

· A full stop closes the door.

Consider the difference:

‘I thought I understood him, but I didn’t.

‘I thought I understood him; I didn’t.’

‘I thought I understood him: I didn’t.’

‘I thought I understood him — but I didn’t.’

‘I thought I understood him. I didn’t.’

The words are almost identical, but the voice is not. In my teaching days, I’d read work from students which had no punctuation in it whatsoever. It’d just be a string of words which absolutely nothing to give the reader a clue how to read it. I’d ask the students to read their own work aloud - and they would give it the punctuation it lacked in text form. I’d ask them how they expected me [the reader] to know all that if they didn’t bother to tell me with punctuation. I mean - a full stop would have been nice now and then.

Rhythm is syntax made audible

Prosody also emerges from sentence structure. Short sentences create force. Long sentences create flow, or sometimes suffocation. A paragraph of uniform rhythm feels mechanical; variation gives prose its pulse. Again, in my teaching days, I’d read an assortment of texts. Some students believed that the longer the sentence, the better. At some point they’d been told that they needed to elongate their sentences so they’d add clauses or phrases which had no purpose in the sentence other than to elongate it. A favourite technique was to say something and then bung in a comma and follow it with ‘meaning’ … and then repeat exactly what they’d already said, as if that made the writing of higher quality. I’d tell them that if they did that in an exam, all they’d be doing is wasting time and losing marks because they’d be repeating themselves. I’d have students who would, literally, say exactly the same thing three or four times just by writing artificially elongated sentences.

Others would include a variety of sentences, not because it better conveyed their voice, but because they’d been told that they needed a mix of long and short sentences. This is writing for a checklist, not writing to convey either meaning or authorial voice. One memorable student had writing which looked very pretty on the page, very even and, somehow, symmetrical. Then, I realised: this individual was changing paragraph every ten lines … without fail. It had nothing to do with what they were saying at all. It was all about visible appearance: a paragraph should look like this … and it was ten lines in their own handwriting.

The point is that technically ‘correct’ prose can still feel all wrong. It might obey the rules but it is ignoring the music.Good writing is about using structure to create the rhythms needed to enable the reader to ‘hear’ the author’s voice in their heads.

White space and the power of silence

Prosody is not only about what we hear. It is also about absence.

Paragraph breaks, line breaks, and white space slow the reader down. A single-line paragraph can carry more weight than a block of explanation. Silence, used deliberately, becomes part of the meaning and of the way the reader hears the author’s voice as they read.

White space is the writer’s pause.

Word choice and natural stress

Prosody is further shaped by lexical decisions. English naturally stresses certain words more than others.

Anglo-Saxon vocabulary tends to strike harder; Latinate vocabulary flows more smoothly.

Let’s compare:

‘They started the fight.’ (Anglo-Saxon origin)

‘They commenced hostilities.’ (Latinate origin)

Here, we see Anglo-Saxon words are shorter and more percussive whereas Latinate words are longer, multi-syllabic with the stress more delayed.

‘She was afraid’ (Anglo-Saxon origin)

‘She experienced apprehension.’ (Latinate origin).

The word ‘afraid’ lands quickly whereas ‘apprehension’ sort of keeps the reader hovering and a bit distant.

‘We found out the truth.’ (Anglo-Saxon origin)

‘We ascertained the facts.’ (Latinate origin)

Anglo-Saxon words tend to speed a sentence up whereas Latinate words tend to slow it down.

‘You broke the rule.’ (Anglo-Saxon origin)

‘You violated the regulation.’ (Latinate origin).

The Anglo-Saxon voice gives commands whereas the Latinate voice is more bureaucratic.

Let’s give this to Shakespeare for a moment and compare ‘This above all: to thine own self be true.’ with ‘Maintain personal integrity’. Both mean the same thing but only Shakespeare is singing to us. That’s prosody.

In my own writing, I instinctively use this contrast between the Anglo-Saxon and the Latinate. When describing lived experience, I favour the Anglo-Saxon. When describing institutions or systems or abstractions, I favour the Latinate. A good example is in one of my short stories ‘I trashed the boys’ toilets today’ where I write, ‘I hammered, frenetically, on a door.’ That’s very Anglo-Saxon; the reader is meant to ‘feel’ the energy and sense of urgency. I could have written, ‘I engaged in a violent act of destruction.’ That sounds more like a criminal report than a feeling and is much more like something derived from a Latinate origin. Often, I use a blunt Anglo-Saxon verb to drive a sentence and contrast them with Latinate nouns which can make my readers hear the irony which is the voice inside my head.

In ‘The Gladiator’s Loss’, which I’ve included earlier in this blog, there’s a series of short sentences: ‘They had fought hard. They had fought bravely. Blood had flowed.’ This repetition creates a sense of insistence, like a drumbeat or a marching rhythm. Similarly, alliteration and assonance guide the ear even when the reader is unaware of it. Again, let’s quote from ‘The Gladiator’s Loss’: ‘Twisting and turning, thrusting and parrying, running, leaping, ducking, diving …’ These are alliterative clusters – t/t/th/p/d/d.

These choices are subtle, but they accumulate – and it is the accumulation which creates the overall melody.

Why this matters in proofreading and editing

From an editorial perspective, prosody is often what distinguishes competent writing from compelling writing. Punctuation errors don’t merely look untidy; they distort the voice. A misplaced comma can flatten emphasis. An overused dash can make prose breathless. Excessive short sentences can feel hectoring.

Proofreading and editing for prosody means asking not just Is this correct? but ‘How does this sound?’ And, just as important: ‘How does the author intend it to sound?’ Strong writers hear their sentences before they publish them. Strong editors help restore that voice when it falters.

Let’s look at some Shakespeare

A classic example of prosody in Shakespeare comes from Macbeth (Act I, Scene VII), where sound, rhythm, and emphasis mirror Macbeth’s mental turmoil:

‘If it were done when ’tis done, then ’twere well it were done quickly.’

The line appears to follow iambic pentameter, but the piling up of “done” disrupts the smooth rhythm:

If it WERE | done WHEN | ’tis DONE, | then ’TWERE | WELL

This mirrors Macbeth’s inability to think cleanly or decisively while the obsessive repetition of “done” creates a dull, heavy thud. Meanwhile, the comma forces a pause that undercuts the wish for speed:

He wants it “done quickly”

But the syntax keeps stopping him

The sentence resists fluency because Macbeth’s mind is resisting clarity. This is what Shakespeare intended to convey.

If we compare this with another line from Shakespeare. This time, from Twelfth Night (Act II, Scene I), spoken by Viola:

‘I am the man: if it be so, as ’tis,

Poor lady, she were better love a dream.’

This begins with regular iambic pentameter:

I AM | the MAN | if IT | be SO | as ’TIS

When reading this line, actors almost always stress the word ‘am’:

‘I AM the man.’

This is because the stress on ‘am’ asserts identity – a false identity because the line is spoken by Viola, who is impersonating a man. If the actor stressed ‘man’ instead of ‘am’, the line would sound very different, more ironic. It would undermine the impersonation and ruin the plot. Again, Shakespeare has given those reading the parts clues as to how he wants the character’s voice to be heard. This is prosody.

Prosody in Proofreading and Editing

The role of a proofreader and editor is to help writers to convey the voice in their heads to their readers. This is why it isn’t just about correcting spellings and grammar. It’s about understanding both what the author is trying to say and how they want their readers to hear it. That’s why good proofreaders and editors care so much about the author’s voice.

If you want a proofreader or editor to take real care to preserve your ‘author’s voice’, then Verbatim can help.

Precision. Clarity. Verbatim.

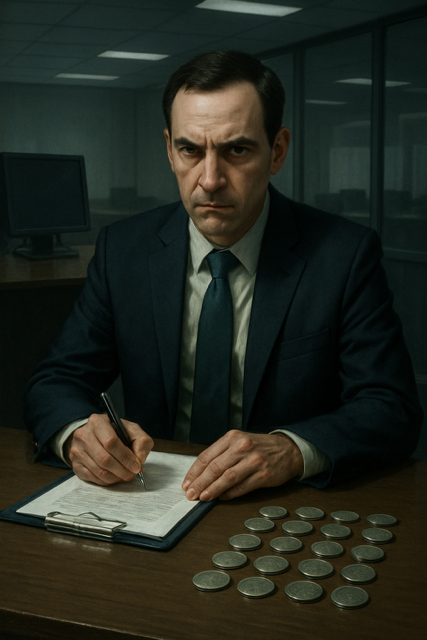

Judas

Judas

Judas looked pious. Pursing his lips, he complained that Mary was wasting money that should have been given to charity. ‘The poor’ said Judas, ‘were his priority: they should come first.’ Mary was so selfish, spending cash on a perfumed unguent - and for what? She’d basically just tipped it all over the floor - and what a damned mess it had made, too. What a show-off that woman really was: just attention-seeking, hoping to get a pat on the head from the boss by a show of sickly sucking up. It made Judas want to throw up. He was satisfied in his sanctimoniousness: that money should have been given to the poor. And, since he was the treasurer, it was his duty to uphold ethical standards in this group and say so. So he did - and he felt good about it.

He might have persuaded the others, too. Judas was so sincere. His face was a pure mask of gravity: ‘Our mission is to help the needy,’ he said. ‘We must do everything in our power to ensure that the naked are clothed, the hungry are fed and the homeless are homed.’ And, with every word, his voice resonated like a bishop announcing the start of Lent. An hypnotic self-righteousness oozed from him and the disciples nodded with approval.

Sometime later, Judas sat in his office. That woman was becoming a problem and he did not know what to do with her. He had thought he’d solved it last year when he’d tricked her into her into accepting a temporary post. No: he hadn’t told her it would only be temporary. He’d left her to find that out … later. He was sure she’d agree and, when it turned out not to be a proper post, it’d be too late for her to do anything about it. In the end, she’d have to accept the demotion and suck it up. But he could not afford to have this miserable wretch in any position of influence. She was too … infectious. Her misery became everyone’s misery.

But, it hadn’t taken more than a few weeks after being given the temporary post for her to start breaching her boundaries and turning what he’d intended as a narrowly defined cul-de-sac into a diving board. She was the architect of this new business strategy. And the damnable thing about it was that she was right. All the research said so. All the experts said so.

But Judas didn’t want her to be right. It was … inconvenient that she was right. Damn! He didn’t want her to be right.

‘Let her alone,’ said the Lord. His calm and authoritative voice pricked the silky smooth and rainbowed bubble which Judas’ sincerity had been blowing. ‘… against the day of my burying hath she kept this.’ What the hell did he mean by that? What burying? Why would Jesus need to be buried? He was only in his early thirties and as healthy a man as Judas had ever seen. Judas had been banking on that when he’d joined the disciples. Whatever you thought of this Jesus and his pretensions, he seemed able to magic up food or money - or whatever was needed - whenever he wanted. And, in these insecure times, that was worth holding on to - even if you did have to put up with a lot of mumbo-jumbo from time to time.

But this? This was too much! That perfumed stuff that Mary had just wasted could have been sold for a small fortune. Where, he wondered, had she got it from? ‘Our priority’ said Judas in a stentorian tone, ‘is the poor. They must always come first.’ Judas was so very deeply sincere that, momentarily, his eyes filled with tears at the thought that the poor had been deprived by this idiotic woman and her stupid idea that Jesus was going to be buried. And how very inconvenient it was for Judas; he could have done with that money for a certain creditor was pressing him hard.

It wasn’t just inconvenient. It was expensive. Judas stared broodingly at his spreadsheet. Three years he was going to have to pay her - and he had nothing for her to do. Everything about Mary was just ‘wrong’. Mary knew far too much to be kept on the factory floor, just turning the machines over. She kept popping up where she shouldn’t be and saying things she shouldn’t say. It was infuriating. There was a ‘right’ way to do things and Mary should shut up and just do it. Worse, people listened to her, like she was some sort of prophet. He needed to rid himself of her … but, how?

Could she be bribed? Judas had possession of the purse. Jesus never checked it. He was too trusting. More than once, Judas had given himself an advance payment and forgotten to put it back. Yes - any payment to Mary would have to be approved by HR - but he was sure he could square it. But - would she take it? She clearly hated this temp job, and she certainly wasn’t going to like what he’d got planned for the next business cycle. But could she be persuaded to go voluntarily? Judas was not sure. If not, could he find a way of pushing her out? Could she be … framed?

The thought hung in the air …

Judas leaned across his desk and faced the high priest: ‘What will ye give me, and I will deliver him to you?’ They bargained for a while, but Judas settled for thirty pieces of silver. It was a fair price. It’d keep him going for a while and allow him to pay off some of his immediate debts. Besides, he rather thought that some of the other disciples were becoming suspicious of him. He’d spotted that Peter watching him very closely last time he’d counted the coins in the bag. The high priest shook Judas’ hand: they were agreed.

That evening, Judas sat watching Jesus as he served at table. Mary’s disturbing WhatsApp filled his mind, and he wasn’t paying too much attention to the conversation. Mary had sounded like she was half-mad. She was clearly stressed out and exhausted: babbling about being broken and having no hope. Was she suicidal? For a fleeting moment, Judas hoped that she was; that’d solve everything. He fantasised about sending a wreath and making a sentimental speech - and then forgetting all about her. Oh fuck! It would be best for everyone if she’d just go!

But … a person in that state of mind could easily make a mistake. If she made just one … he’d have her. If he could find so much as one typo out of place, one anomaly … and he’d have her. Whatever it was, he’d frame it in the worst possible way. There’d be no defence. Whatever it was, he’d ramp it up. If there was any exonerating evidence, he’d suppress it. And she’d be gone, ‘processed out’ in a flash!

What was that? Jesus had just said something about someone betraying him. A vibe of shock rippled through the assembled disciples. Had the Master just hinted that one of them was a traitor? Ever alert to the danger of discovery, Judas put on his most pious expression. Deflection - that was the way. He was sure no-one had seen him with the high priest. ‘Is it I?’ he asked, his eyes widening in innocence. Jesus stared right at him, right through him - and, as their eyes met, Judas knew that he did know. He’d always known.

Mary stared into Judas’ eyes. She saw no sympathy. What had she done? She did not know. But - it didn’t matter - Judas had composed his story in his mind. Mary was negligent. She had failed in her duty. He had found a scrap of paper with her signature on it and he knew he could use it to weave a story good enough to justify firing her. It wasn’t true - she’d just failed to spot an anomalous entry in the ledger and signed it off without checking. It was the sort of mistake anyone might make - but no-one would care. ‘Fraud’, that was how to put it. That sounded really, really bad. ‘Our priority is to help the poor’ said Judas, ‘not to help ourselves.’ ‘The poor and needy must always come first.’

The leaves rustled. Judas strode into the clearing. He walked straight up to Jesus and, with his arms stretched wide, embraced him and planted a kiss on his cheek. That was the agreed signal. Within seconds, Jesus was surrounded by armed guards and swiftly marched away.

A million light years away, Mary was also escorted from the corporate premises.

Judas sighed with satisfaction at a plot well-conceived and well executed. And … morally justifiable in every way. A faint pink glow of self-righteousness emanated from Judas as he pressed ‘save’. That was the paperwork sorted - and the processing had begun.

…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..

It was later that the doubts crept in. What had Jesus actually done? Nothing. Judas recalled the miraculous feeding of the 5,000. He saw blind Bartimaeus skipping down the road. He saw the man who had been sick of the palsy carrying his bed out of the door. He watched Lazarus ….

Suddenly, he felt an unendurable pain in his heart. It were as if an invisible hand had punched inside his chest, grabbed it and started to twist it violently, squeezing and pulling and contorting it. The agony was intense. His knees became weak and he began to choke. He was violently sick. He shook as if he’d been doused in ice-water. The thirty pieces of silver lay on the table in front of him. He could not bear to look at them. They seemed to be burning into his retina. He closed his eyes. They were still there - a fiery image etched on the inside of his eyelids. There was no escape! An explosion of anger and he swept those taunting coins onto the floor. But, there, in the candlelight, they still winked accusingly at him.

The words of Mary’s last WhatsApp echoed in Judas’ mind: ‘utterly unwanted for anything, it seems …’ She was clearly at the end of her emotional resources. Her hopelessness seemed pervasive. Good - that meant she’d be unable to put up a fight. Weak and vulnerable, Mary would be helpless: an easy victim. Judas fell into a drowsy sleep.

He lay in a pool of his own blood. His intestines writhed like snakes and his conscience seared like a hot iron. There was no forgiveness possible for such a sin. To have betrayed the Son of God with the deception of a kiss … Judas could not live with himself. He sought only the oblivion of death. But was death really the end? Once more, he thought of Lazarus …

In his delirium, Judas heard a cool and collected HR voice: ‘It’ll be fine, as long as we followed the correct process.’ Process, process, process - the word seemed to reverberate on a repetitive loop. ‘It’s not about truth. We just need to make sure the paperwork tells our story. As long as it labels Jesus as a fraud, we’re in the clear. No-one will ever know what really happened. He’ll be gone and everyone will forget him. Even the disciples will believe it, if it’s in the minutes. Our corporate letterhead carries authority and authority is always believed, unquestioningly … ‘

… except by Mary. She had followed Jesus right up to the cross itself, never doubting his divinity. For an instant, that thought nagged at Judas. But then he remembered that Mary wasn’t there anymore, was she? She, too, had been ‘processed’. No need to worry about the pang of conscience, then.

Judas smiled. He felt relieved. He didn’t need forgiveness. ‘Process’ was sufficient to cover up his sin and the paper trail was complete.

If you write fiction, Verbatim can help you by proofreading and editing your manuscript to make sure that your story has the impact you want it to have on your readers.

Precision. Clarity. Verbatim.

The Power of a Twist in the Tail - and why Essays shouldn’t have one

AI - generated picture

Whatever you are writing, it’s always important to remember that readers anticipate. Thus, the opening to your piece sets the expectation for a reader.

In fiction, a twist in the tail works because of this anticipation.

Readers instinctively project forwards, assembling clues as they go. A good twist doesn’t come out of nowhere. It reconfigures what the reader thought they understood. The clues were there all along, but they add up to something unexpected. That’s why a twist is so satisfying: it surprises us and, yet, makes perfect sense in hindsight.

But in academic or professional writing, the opposite is true.

An essay should never have a twist. Your reader should not be misled, wrong-footed, or jolted off course. Instead, they should be taken on a journey that is clearly signposted at the outset. Your introduction establishes the destination; your structure provides the route. By the time they reach your conclusion, the reader should feel informed, not ambushed. Your conclusion should re-visit the argument made in the introduction and, essentially say, “There! I told you I was right at the start.” There should be no surprises.

Both genres of writing share the quality of the reader’s anticipation. But they use it to achieve different outcomes.

Whether you are writing fiction or non-fiction, Verbatim can help you refine your text.

Precision. Clarity. Verbatim.

Let’s talk about Bill …

Teaching can be a brutal profession. Young graduates, filled with evangelistic zeal, are inspired to enter the classroom ‘in order to make a difference’. Some love their subject and want to share that love with the next generation. Others want ‘to give something back to society’. Some love the ‘cut and thrust’ of classroom banter, swear that they ‘like children’ or have a passion to ‘make the world a better place’. Invariably, new teachers are idealists.

Yet, many do not make it through 5 years in the profession. The classroom can often resemble something more akin to a battlefield than a place of learning. Instead of intellectual autonomy, the teacher becomes an agent of institutional control: checking conformity with uniform standards, delivering pre-packaged lesson materials and talking in endless meaningless jargon.

The classroom itself is a lonely place. Lonelier than they imagined it would be. Lonelier than anyone would imagine it could be with all those bodies packed together like sardines in a tin. Despite constant rhetoric about collaboration and teamwork, in the end, the teacher is on their own for most of a day. Outnumbered, he has to muster the emotional energy required to be the dominant force in the room for hour after hour. All teachers know that they may not actually be the smartest, most talented or strongest character in that room. And, if they are not teaching their own subject, they may not even be the most knowledgeable. That comes as an almighty shock: new teachers expect to be teaching the subject they signed up for - typically the one in which they have a degree. They anticipate being able to wow their juvenile audience with their hard-earned expertise. ‘At least there’, they think, ‘I will have the advantage.’ No - modern schools frequently take the view that any ‘teacher’ can teach ‘anything’ and a young person, barely out of school themselves, finds that they are trying to explain something they simply do not fully grasp themselves. Unless you’ve been there, you cannot really understand how totally disempowering that is. A PE teacher is told to ‘teach’ French because 5 years’ ago they got a GCSE in French. An Art teacher is told that they have to ‘teach’ DT: Resistant Materials or Food or Graphics. Since when does a degree in fine art equip you to teach Food? A Chemist is directed to Maths. Or a Drama teacher to Music or IT. You feel utterly vulnerable.

I’ve known teenagers who have been sufficiently self-aware to also know that - and who have been prepared to use their own charisma, intellect, social credibility and strength of will to deliberately undermine a teacher. When that happens, the teacher becomes a victim. A class of harmless-looking children can behave like a feral pack; they ‘hunt’ their teacher; they attack, relentlessly and mercilessly. And many a young teacher has been driven from the classroom, their idealism torn to shreds, by the fear of being savaged several times a week, or even a day, by a class who has them ‘on the run’, often surreptitiously led by a single. malicious and dominant character who remains hidden and unseen beneath the chaos. Experienced teachers who’ve fought this fight - and won - can often spot the real malignant force which is persistently working away to destroy not only the classroom environment, the learning of the majority, and the teacher’s own self-esteem. An experienced teacher watching the dynamics of a classroom in which the teacher is a novice can often see what’s really going on in a kind of sub-text.

What this means is that the life of a classroom teacher can be like living on a knife-edge. A teacher’s senses can be on hyper-vigilant alert, all day. Every sound may signal danger. Every move an imminent crisis. At any second, the teacher may be called upon to react, in an instant. It’s easy to make a mistake. There is no space for relaxation. And, if you know that trouble is coming down the corridor towards you in the form of that class you truly dread, the anticipation is as bad as the experience. Indeed, it’s the fear of tomorrow that keeps many teachers awake at night. That sense of relief on realising that the student, whose face haunts your nightmares, is missing today is quite something. I imagine that it’s a bit like going to receive some test results and discovering that you haven’t got cancer after all.

That metaphor of cancer is incredibly apt. Being in a classroom, hour after interminable hour, and having your self-esteem eaten away by that nagging feeling of vulnerability: insecurity, anxiety and that knowledge that you are absolutely not in control of the situation, is like living with a cancer that is insidiously corroding your very being. You are truly an imposter. You are a clown with thick, caked-on make-up which is disguising that ever-diminishing figure which is the real you.

And if you come to work ill? They sense it. There are classes which are super-nice. Lovely human beings who metaphorically cuddle you in a blanket of sympathy. But the others? They have no pity. They will exploit the poor teacher’s vulnerability. These are dangerous times because this is when the unwary teacher can make an error - and the next day find themselves in trouble because they ‘were a bit snappy’ or missed something they should have noticed. A parental complaint comes in and they find themselves having to defend an action or something they said when they were really too ill to be in that tense and pressured environment but they’d turned up out of sheer conscientiousness, thinking they’d cope. Do school leaders show sympathy? Of course not. They behave as if the poor teacher’s vulnerability did not exist. Struggling in with a sinus infection, a stomach upset or, even, hayfever doesn’t cut the mustard. ‘If you aren’t fit, you should have stayed home.’ Very true. But, if you stayed home every time you weren’t 100% up to snuff, especially given that there are several nights in a week when your fears for tomorrow mean that you barely sleep, you’d be in trouble for triggering an attendance warning. You can’t win. If a teacher has five lessons in a day and only one of them is the class from hell, the risk of the day ending up as a catastrophe is 100%, not 20%.

Then, there is the workload. Teachers are always complaining about workload. Yet, they rarely define what that means. A full day in the classroom is emotionally exhausting. It’s impossible to convey to anyone who hasn’t done it how the adrenaline, which has fuelled the teacher all day, suddenly drains as the end-of-day bell screams out and the children hurtle from the room and a sudden silence descends. It leads to a ‘downer’ - which has to be filled by something. Alcohol? Sugar? Compulsive exercise? There are many ‘drugs’ which teachers use to combat this barely recognised, but all too real, sensation. The most benign mean walking with a dog or engaging in an absorbing hobby. The most insidious is alcohol. Many teachers drink too much. It’s so easy to reach for that glass of wine, that shot of whisky, that gin and tonic - just to aid post-school relaxation. But, over a week, that alcoholic consumption is cumulative, and, over years, it’s easy for that one glass to become two, or three - or the whole bottle. There are teachers who would be horrified at the thought but, in truth, by their mid-40s, they have become functioning alcoholics.

All this is cumulative and it makes a normal family life very difficult. Teachers often find that they can’t ’switch off’; their minds race, their fears about what will happen tomorrow and insecurity about whether they did the right thing all whirl around in their minds. Insomnia is common. Irritability with family inevitable. Many teachers actually, and totally unintentionally, neglect their own children whilst spending their entire working lives helping others. Yes: they’d be horrified at the thought and absolutely do not recognise it in themselves. But a teacher who spends every weekend working, and leaving their partner to deal with their own children’s problems is not being a good parent. Children of teachers often spend hours in empty classrooms while mum or dad attends meetings or works after the end of the school day. Such children are patient but few of them will ever voluntarily enter the teaching profession themselves. Some do - but, for many, that decision is internalised rather than understood. And marriages fail because of it. What husband is going to respond well to a wife who comes home every night and does 2-3 hours of work, barely talking to him, and then does the same all weekend, leaving him to ferry the children to swimming or football or dance class? What wife is going to tolerate a lifetime of a husband who talks about nothing but school - if, and when, he talks to her at all - while she cooks and cleans and washes and deals with her children’s every day problems, while trying to hold down her own full-time job? Such relationships inevitably come under strain. Lots of teachers marry teachers. It’s the only way - and children where both parents are teachers really can pay that price. Some families make it work, of course. But many break under the strain. More often, a teacher decides that leaving the profession is the only way to be a good parent or to save their marriage.

Teachers don’t get enough daylight, or fresh air. This is especially true in winter. Too many hours under electric lighting can give rise to semi-permanent headaches. They don’t get breaks. Gulping down a scalding cup of tea in the ten minutes of mid-morning break is not a break, especially when the choice was between this abominable beverage and going to the toilet. Teachers must have strong bladders for it is often impossible for them to relieve themselves for hours. Children demand to be able to go to the toilet whenever they want and loudly proclaim that it’s their ‘human right’ to do so. OK - but their poor teacher must stand there and hold it, for he can’t indulge himself and pop out for a pee just because nature has called on him, too. And - God forbid that you are a young female teacher at a certain time of the month: that tell-tale ‘blup’ warning you that you must not sit down until you’ve been to the toilet - and that possibility might be two hours away.

Lunchtimes are too short. Thirty minutes? If the teacher wishes to speak to a child about something, tidy up and get ready for the afternoon or make a private phone call, there’s no time to eat. Many a teacher has nothing to eat from 8.30 in the morning until late afternoon. No time. And - there’s that rush for the staff toilets again.

Oh - and I forgot - I’m supposed to be talking about workload. The heaviest and most relentless part is, of course, marking. Teachers from an older generation talk of long lunches and more non-contact time in which marking could be fitted in. But today’s frenetic days mean that there’s no time in the school day. Marking must be taken home or it will not get done. Many a teacher, who tries to balance work with family life works late into the night, after their own children have gone to bed … marking. In my teaching days, I’ve marked til 2 am on a Saturday night, marked while walking in fields on a Sunday afternoon and marked during mealtimes.

Teachers also complain about planning. Yet, like marking, planning is part of the job. Even in the era of the classroom delivery model, no teacher can afford to rock up to the classroom without having at least read what they are supposed to be delivering. But many do - it’s easy to spot those who are ‘winging it’. And the children know. Of course they do; it undermines their respect for a teacher when they can obviously see that the teacher hasn’t a clue what is on the next slide. And cares even less.

Then there’s the scrutiny. It’s hard enough to be alone in the classroom. Harder still to be constantly alert to the imminent arrival of someone with a clipboard. You know that the word ‘support’ in teaching is largely code for ‘checking up on you’. Every school has its own version. Did you follow the entry routine correctly? Did you make sure that the children correctly laid their equipment out on their desk? Did you use the approved wording for your lesson objectives? Did you make sure to give praise points to at least three children? Did you monitor skirt length as the children entered the classroom? Check for jewellery? Was the ‘house badge’ correctly displayed? The House system inculcates pride and a sense of belonging - but, apparently, that escapes the average teenager, who will, if not relentlessly checked five or six times a day, dispose of said insignia and, showing a streak of malevolent individualism, walk around ‘un-branded’. It’s the same with uniform. Despite being persistently told that it gives them a sense of community, they will insist on pulling their shirts out, twisting their ties into bizarre shapes and wearing shoes with non-regulation bits of decoration. In the days before clip-ons, I spent many an early afternoon untangling a tie which had been used at lunchtime as ‘handcuffs’ or tied round the head as a bandana. It’s almost as if they don’t want to ‘belong’ to a club they’ve been conscripted into. Strange creatures! But for the teacher? Ah … there are endless protocols to adhere to, driven by fad, by external educational consultants and the whims of school leaders.

And I’ve not even talked about the data mania. In many schools across the country, each child is given a plethora of ‘targets’. Where these targets are derived from is mysterious and their statistical validity unknown. All the average teacher is told is that they define a child’s ’potential’ in your subject and, despite having virtually no autonomy whatsoever to deviate from the externally imposed teaching programme or the imposed protocols regarding delivery, the teacher is told that it’s their responsibility to ‘ensure’ that the children reach these divinely-inspired ‘targets’. Responsibility without power is a recipe for cognitive dissonance and a source of great psychological stress. How many teachers have been told that the targets that have been handed down by holy writ to their students are both ‘aspirational’ yet, also, the ‘minimum expectation’? Is that even possible? How many more have been told that 70% (or even 100%) of their students must achieve ‘above average’? And, if those students fail to achieve this miraculous feat? Well - that’s the teacher’s fault, obviously. It’s a strange concept.

It’s an even stranger world. Most jobs are based on the premise that wages are awarded in return for hours worked. It is beyond the comprehension of the non-teacher to contemplate doing work for no pay. Whether that’s a professional, paid by the hour, or a factory worker, paid for the shift. No-one expects to be told that it’s an ‘expectation’ that they put in extra hours of work for no pay at all. It’s routine in teaching. So - you’re paid to do classroom-facing duties for 23 hours per week and someone comes along and tells you that you’re expected to do two more, after school, hours. Will you get paid for them? No. It’s an ‘expectation’. And the word ‘expectation’ is thrown around like litter in a strong breeze. Run a club? When? In the 30 minute lunch break? Another ‘after school hours’ commitment? Run a revision session during the holidays? Am I going to be paid for it? No - it’s your ‘duty’ to ‘do everything you can’ for the children taking exams. And it’s largely performative. Who, in their right mind, thinks that, after more than a decade studying Mathematics, it was that two-hour session in the Easter holidays which made all the difference? It never ceases. And if you refuse - as you are entitled to do - it’s a black mark. This teacher ‘lacks commitment’. Or worse - they’re ‘unprofessional’.

Oh boy! Is that phrase banded about in teaching. What it really means is that the teacher stands their ground regarding these non-contractual ‘expectations’ or criticises a policy decision, a curriculum decision - any decision. It means that they went home at the end of the school day, rather than stay for extra hours of unremunerated work. Perhaps they expressed frustration with a petty imposition, or insisted on a basic entitlement, like having lunch or dared to go on holiday at Easter rather than run unpaid revision sessions. Most commonly, it means that they simply disagreed with the leadership over something. At worst, it is because you let the Panglossian mask slip: the public persona of teaching is that ‘Everything is for the best in the best of all possible worlds’. The 11th commandment is: ‘Thou shalt radiate positivity at all times.’

‘Just make three positive phone calls home each week’, they say. Nice idea. But each one of them can be a 20 min conversation. The parent is delighted that their child is doing so well. They’re pleased you rang and, while they’ve got you on the phone, they’d just like to mention … Three phone calls equals another hour’s work … for no extra pay. ‘And - don’t forget to log the call with a brief description of what was discussed’. That’s another half hour. It quickly mounts up.

And the justification for all this? Well, the standard teaching contract contains that catch-all concept of having to do anything necessary to fulfil their duties. And who defines that? As Shakespeare says, ‘There’s the rub.’ It’s as long as a piece of string.

But what about Bill?

What? You thought I’d forgotten? No. Bill was one of the best teachers I’ve ever met. He taught English.

More than that, Bill was the single best manager of people I’ve ever met in my life. He was a Deputy Head from the old school. Started teaching in the mid-70s in a boys’ grammar school and rode the tide of comprehensivisation to become a pivotal figure in everyone’s life. Bill had a saying “No-one has the right to make anyone else’s day miserable.” Bill would shadow a single child around school to make sure that he wasn’t being bullied. He’d make sure that he knew what each child coming into Year 7 from our feeder schools needed. He knew the community: the families and the problems.

But - Bill also cared about the staff. If any teacher had a problem, Bill would be there. Bill had a way of dealing with the most awkward of characters. He massaged bruised egos, alleviated the anxious, calmed the headstrong and lifted up the weary. He solved problems which seemed intractable. When asked, I said that Bill was the ‘oil’ which made the school function. He was.

He was kind, considerate, funny, clever, charismatic - and gentle. That’s not to say that he couldn’t terrify the children. I had many a child ask if they could stay in my classroom at lunch. Why? Because they had English after lunch and they hadn’t done Bill’s homework. They’d not done mine either - but, clearly, I did not inspire the same kind of respect as Bill.

Yet, on his office wall was a handwritten copy of the old proverb: “If you have two loaves of bread, give one to the poor. Sell the other and buy hyacinths to feed your soul.” That was Bill: a good man, a fabulous leader and a truly inspirational teacher.